"Countless Lives Inhabit Us" (Pessoa)

Here is Fernando Pessoa’s “Countless Lives Inhabit Us”:

Countless lives inhabit us.

I don’t know, when I think or feel,

Who it is that thinks or feels.

I am merely the place

Where things are thought or felt.

I have more than just one soul.

There are more I’s than I myself.

I exist, nevertheless,

Indifferent to them all.

I silence them: I speak.

The crossing urges of what

I feel or do not feel

Struggle in who I am, but I

Ignore them: They dictate nothing

To the I I know: I write.

I happened to flip Pessoa’s Selected Poems open to this page the other day, and was struck by how perfectly the poem embodies the notion of the “decentered self,” that slippery theoretical construct that was all the rage back in the eighties, and well into the nineties, when I was slogging through grad school. I guess the phrases “decentered self” or “decentered subject” are not quite en vogue by now, but certainly some variant of the concept lives on in other characterizations of postmodern subjectivity like the “posthuman.” Pessoa give us yet another case of a poet getting there before the theorists (and of course Rimbaud was there even earlier with Je est un autre), not just in this poem, but in his whole poetic practice, since he crafted entire personal histories and poetic styles to go along with the set of “heteronyms” under which he wrote. The Selected is divided into separate sections for each of these heteronyms, giving us “Alberto Caeiro: The Unwitting Master,” “Ricardo Reiss: the Sad Epicurean” (the “author” of the poem above), “Alvaro de Campos: the Jaded Sensationist,” and finally “Fernando Pessoa-Himself: the Mask Behind the Man.” I haven’t read enough of the poems to get a clear sense of all these alter egos and how they relate to one another, but what hits me in browsing around the book is how nearly unavoidable the sense of fragmented and multiple identities must be for just about any writer, or so it seems to me. I mean, who the hell knows what’s going to come out when you sit down to write? The remarkable thing is that it took so long (until nearly the twentieth century) for the problem to arrive at full expression, as it does in “Countless Lives Inhabit Us.” And despite Pessoa's comfort with heteronyms, this "decenteredness" is clearly a problem in the poem; Pessoa/Reiss gives us a real struggle for mastery, a willed subsumption of those “crossed urges” under the “I” doing the writing at the moment. But of course the victory is temporary, accounting for just one poem under just one heteronym, and the struggle begins all over again with the next writing. Some poems, of course, do refuse the struggle and make a virtue of their decenteredness, but even these need a compelling reason for existing in just the form they do, which is another (displaced) sort of struggle for identity.

~

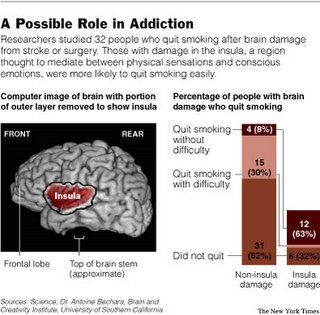

Anyway, if I am at all interested these days in a theoretical take on this issue, it is to wonder how the concept of the “decentered self” might intersect with a whole set of developments out of cognitive science having completely different intellectual antecedents (i.e., these developments come out of neuroscience rather than “French theory”). I have in mind, for example, Daniel Dennett’s “multiple drafts” theory of consciousness in Consciousness Explained. And thus I end up not too far from yesterday’s post, with Damasio’s discussion of the insula as a brain region that seems to be involved in “mapping” a whole set of disparate subcortical bodily signals into a “coherent” experience of emotion.

Countless lives inhabit us.

I don’t know, when I think or feel,

Who it is that thinks or feels.

I am merely the place

Where things are thought or felt.

I have more than just one soul.

There are more I’s than I myself.

I exist, nevertheless,

Indifferent to them all.

I silence them: I speak.

The crossing urges of what

I feel or do not feel

Struggle in who I am, but I

Ignore them: They dictate nothing

To the I I know: I write.

I happened to flip Pessoa’s Selected Poems open to this page the other day, and was struck by how perfectly the poem embodies the notion of the “decentered self,” that slippery theoretical construct that was all the rage back in the eighties, and well into the nineties, when I was slogging through grad school. I guess the phrases “decentered self” or “decentered subject” are not quite en vogue by now, but certainly some variant of the concept lives on in other characterizations of postmodern subjectivity like the “posthuman.” Pessoa give us yet another case of a poet getting there before the theorists (and of course Rimbaud was there even earlier with Je est un autre), not just in this poem, but in his whole poetic practice, since he crafted entire personal histories and poetic styles to go along with the set of “heteronyms” under which he wrote. The Selected is divided into separate sections for each of these heteronyms, giving us “Alberto Caeiro: The Unwitting Master,” “Ricardo Reiss: the Sad Epicurean” (the “author” of the poem above), “Alvaro de Campos: the Jaded Sensationist,” and finally “Fernando Pessoa-Himself: the Mask Behind the Man.” I haven’t read enough of the poems to get a clear sense of all these alter egos and how they relate to one another, but what hits me in browsing around the book is how nearly unavoidable the sense of fragmented and multiple identities must be for just about any writer, or so it seems to me. I mean, who the hell knows what’s going to come out when you sit down to write? The remarkable thing is that it took so long (until nearly the twentieth century) for the problem to arrive at full expression, as it does in “Countless Lives Inhabit Us.” And despite Pessoa's comfort with heteronyms, this "decenteredness" is clearly a problem in the poem; Pessoa/Reiss gives us a real struggle for mastery, a willed subsumption of those “crossed urges” under the “I” doing the writing at the moment. But of course the victory is temporary, accounting for just one poem under just one heteronym, and the struggle begins all over again with the next writing. Some poems, of course, do refuse the struggle and make a virtue of their decenteredness, but even these need a compelling reason for existing in just the form they do, which is another (displaced) sort of struggle for identity.

~

Anyway, if I am at all interested these days in a theoretical take on this issue, it is to wonder how the concept of the “decentered self” might intersect with a whole set of developments out of cognitive science having completely different intellectual antecedents (i.e., these developments come out of neuroscience rather than “French theory”). I have in mind, for example, Daniel Dennett’s “multiple drafts” theory of consciousness in Consciousness Explained. And thus I end up not too far from yesterday’s post, with Damasio’s discussion of the insula as a brain region that seems to be involved in “mapping” a whole set of disparate subcortical bodily signals into a “coherent” experience of emotion.